Native rabbiteye blueberry cultivars are bearing fruit thanks to last month's featured Southeastern blueberry bees. (Photo by Ellen Honeycutt.)

Chapter News

What a fruitful month we had in May! There are now six forming GNPS chapters that have chosen their start-up committees, made plans to meet, and are going about the business of setting up new GNPS chapters to serve members and the public in their local area. Chapters are forming in these areas; Athens-East Piedmont, Augusta CSRA, Intown Atlanta, Macon, North Metro Atlanta, and the North Georgia Mountains. If you are interested in being part of one of these chapters, just complete the Chapter Affiliation Form on the GNPS website.

What if there isn’t a chapter in your area?

We can help you get one started! GNPS doesn’t decide where new chapters are formed, our members do! If there are ten or more interested GNPS members in your area, and a few people who will serve on the start-up committee to tackle the upfront administrative paperwork, you can start a new GNPS chapter. To get an idea of what it takes, check out the Chapter Quick Start Guide on the GNPS website. We make it as easy as possible to get things done with “how to” guides and step-by-step instructions, and the Membership/Chapter Relations committee to assist you all along the way.

How long does it take to get a chapter started?

It depends! There is no requirement to get the chapter up and running in a certain amount of time. There also isn’t a requirement that the start-up committee spend a certain amount of time each week, each month, etc. The timetable can vary according to the time it takes for interested members to accomplish it. Forming chapters can have meetings, field trips, programs and other activities while they are in the formation stage, in fact, we encourage it!

Chapter Boundaries

Did you know that chapter boundaries don’t really exist? Any member can affiliate with any GNPS chapter. Your city or zipcode are irrelevant when it comes to choosing a chapter. Even if a chapter isn’t the closest one to your home, if you want to be part of the chapter, you can! When you choose to affiliate with a chapter, part of your membership dues are paid to the chapter in the form of an annual rebate. Your membership dues actually help fund the programs and activities of your chapter. If you choose not to affiliate with a chapter, all of your membership dues are invested in programs at the state level.

Chapters and GNPS

Chapters are the conduits through which GNPS reaches members and achieves goals at the local level. As such, GNPS makes a significant investment in chapter support to ensure chapters are successful and have the resources they need. GNPS provides chapters with financial contributions, insurance, website support, a membership database, technical tools, training, and support for chapter leadership and members. Together we can make a difference by promoting the stewardship and conservation of Georgia’s native plants and their habitats.

Other Questions about Chapters?

If you have other questions about chapters, or ideas you would like to share, please contact us at membership@gnps.org, we’d love to hear from you!

Two upcoming virtual events

Doug Tallamy webinar

The Master Gardeners of Central Georgia invite members of the Georgia Native Plant Society to join us for a webinar featuring Doug Tallamy. Many GNPS members have heard Dr. Tallamy speak, and it's good to hear his latest findings and ideas. We hope you'll join us.

Pre-register to receive webinar link by clicking here: REGISTER NOW. Sponsored by a generous donation. Free to all registered attendees.

Cullowhee

The Cullowhee Native Plant Conference has been holding an annual summer conference since 1984. For 2021, the conference will be virtual on July 16-17 and registration is now open.

This virtual conference is a great way to participate if you were physically unable to attend in the past. Although we'll miss the networking of an in-person conference, the slate of presentations is still a valuable experience and the line up looks great. You can participate live or watch the recorded sessions for up to 6 months afterwards. And don't worry about missing the opportunity to get a t-shirt, the option of purchasing one is still available (unisex style only).

GNPS will once again be sponsoring student/beginning professional scholarships, so students and beginning professionals should apply before June 6th to take advantage of the many scholarships offered by organizations across the southeast. REGISTER NOW.

|

|

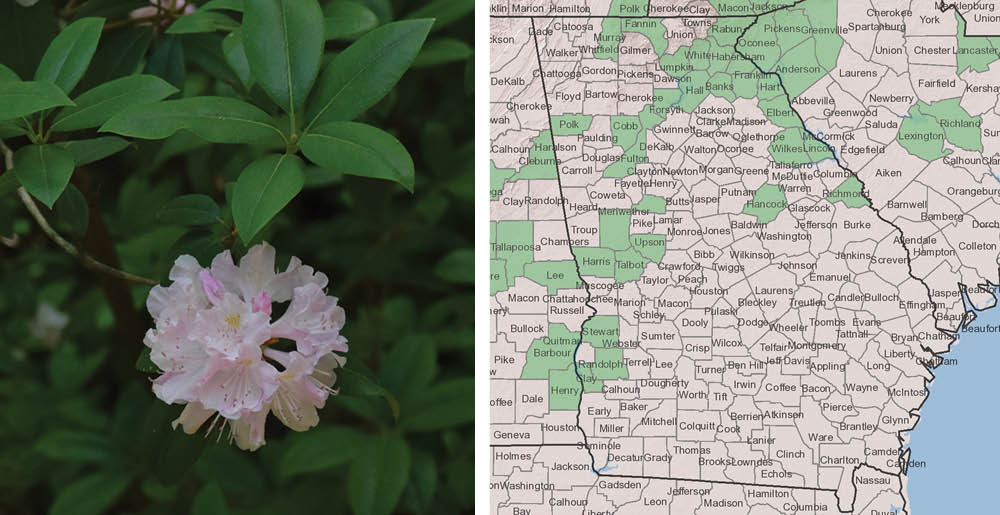

Plant Spotlight: Rhododendron minus

Ellen Honeycutt

The genus Rhododendron consists of native azaleas (which are deciduous) and the plants commonly referred to as rhododendrons (which are evergreen). The smallest of the evergreen rhododendrons is one called Rhododendron minus. It looks a bit like a native azalea but it has leaves that stay on the plant all winter, with fresh ones emerging in the spring.

I enjoy finding it in natural areas in May and June and have been delighted recently to find it in the metro Atlanta area in several locations: Blue Heron Nature Preserve (on the Blueway Trail) and Vickery Creek Trail at Roswell Mill (all these photos are from Vickery Creek). I’ve also seen it at Providence Canyon State Park in southwest Georgia and at FDR State Park in middle Georgia.

It seems to rarely be offered for sale so we may have to be content with admiring it in the wild. At the Roswell location, it was high on the slopes above the creek, mixed with mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia), bigleaf magnolia (Magnolia macrophylla), sweetshrub (Calycanthus floridus), and smooth hydrangea (Hydrangea arborescens).

R. minus and its native range map. Map is © 2014 Esri | USDA-NRCS-NGCE & NPDT. (The PLANTS Database, 06/01/2021. National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC USA.) Photos by Ellen Honeycutt.

Native Fauna Need Native Flora: Red-cockaded Woodpecker (Picoides borealis)

Deborah Ashley

In 1970, the red-cockaded woodpecker was among the first species to be listed as endangered. This was because of the destruction of the flora, thus the habitat, that it desperately depends on for nesting cavities. This habitat is mainly the longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests, but also other southern pines forests such as loblolly (Pinus taeda), and slash (Pinus elliottii).

The adult birds are about 7 inches long and have a wingspan of 15 inches. They live in family units of the breeding pair plus some of the males from a previous clutch. The males, called helpers, assist in incubating the eggs, which takes from 10 to 14 days. After hatching, the nestlings are fed by both parents and these helpers for up to six months. The name, cockaded, comes from a red strip running along the black cap on the males. This common name came about in the 1800’s and referred to a ribbon or other adornment on a hat.

Left: Red-cockaded woodpecker feeding (photo by U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Southeast Region). Right: Red-cockaded woodpecker in flight (photo by Martjan Lammertink / U.S. Forest Service).

If you have never seen a red-cockaded woodpecker, it is because they are rarely visible except when the males are having territorial disputes or during breeding season. And it could also be because their range in Georgia is below the fall line of the state. They depend on a fire ecosystem to burn the underbrush where these pines exist, either by lightning or man-made prescribed fire. This greatly reduces the number of hardwood trees in the pine forest.

Red-cockaded woodpeckers nest in cavities of mature pines (80 to 100 years old) that have been infected with a fungus called red heart fungus (Phellinus pini). This fungus softens the heartwood and makes it easier for the woodpecker to carve out a cavity for its nest. They are the only woodpeckers to live in live trees. They protect their cavity by picking around the edge of the cavity entrance so that sap will run down the tree under their nesting site. This discourages the snakes that might climb the tree and raid their nests.

Because of their ability to excavate many cavities in their territory, this woodpecker is known as a keystone animal. They create cavities for many secondary-cavity users, such as other birds, snakes, lizards, squirrels, insects, and frogs.

The good news is that the U.S. Forest Service and the Department of Natural Resources, in states where these birds reside, have implemented management techniques that have stabilized and increased the number of red-cockaded woodpeckers. These programs include installing artificial cavities for the birds, as well as cavity entrance restrictors. These agencies have also begun programs of prescribed fire, control of woody vegetation and even translocating birds to more suitable habitat. These techniques not only help the red-cockaded woodpecker, but also benefit many additional species of native plants and animals that need this type of habitat. So the future of red-cockaded woodpeckers is looking encouraging!

Georgia Native Goes Native – How on earth did that happen?

Amy Blackmarr

The following article is from a newly minted but avid Georgia Native Plant Society (Coastal Plain Chapter) member, who shares her experience leading into changing the world through native plants. Her journey is her own and her writing style is unique, providing an entertaining and insightful look into her life and how she arrived where she is today. Amy is a Madison A. and Lila Self Fellow of the University of Kansas, holds a doctorate in English, and is an award-winning Georgia author. — Greg Lewis, GNPS-Coastal Plain Chapter Board of Directors

Folks in the native plants advocacy community I recently joined have been asking me how, after decades in Kansas and then Savannah as a writer, a library cataloger, a real estate closer, a grocery store cashier, a legal secretary, a zen monk, an employment agent, an insurance clerk, an aspirant to the Episcopal priesthood, and some other things, I ended up in Tifton with a pruning business that insists on using native plants to replace the dead, dying, and out-of-control exotics-ridden landscapes I’m hired to hold back. I tell people it’s pruning, but I really think of it as aesthetics management, considering the expanding overlordship of plants like the stubborn knee-high thatch of Confederate jasmine and creeping fig I had to kick out of the ground with my feet.

But like one friend says, “Amy’s Aesthetics Management” takes more words to explain than you can fit on a business card, so I just call it Amy’s Pruning.

How this new venture started was, I’d say that like many people in the rural South, gardening runs in the family. I remember helping my grandmother dig turnips and pick strawberries in her back yard in Ocilla when I was little, remember picking beans and watermelons and blackberries at our farm, remember stripping the husks off sweet corn in the field and eating it there raw, remember eating peanuts left behind after harvest, walking the rows with my dog in fall. My aunt and cousin are both master gardeners in Atlanta.

But it was my sister who first started urging me to build native plants into my Savannah yard when I was living there. She got kind of zealous about it while she was landscaping her own place with natives, so because it pains me to disappoint my sister, I put out some native azaleas, an oak leaf hydrangea, a beautyberry, some bee balm, a Stokes aster…but I was haphazard about it. I wasn’t really into the science but I felt sort of obligated, kind of like recycling, you know. My cousin sent me a Virginia sweetspire. I had a sand plum. Some coastal rosemary (it died). A redbud (it also died). Other things.

I also planted, I’m embarrassed to confess, a variegated privet and some mahonia, Mexican violets, Australian tea trees, pampas grass – a lot of nonnatives, some invasive, some already there that I just kept fertilizing. I’d never do that now, but at the time I wasn’t really thinking that hard about it. I just liked having my hands in the dirt. I’ve always preferred outdoors to in, and I like being surrounded by branches. I used to hide in the bamboo when I was a kid. I like the smell of damp leaves and dirt, pine, earth. I don’t mind having dirty fingernails and getting scratched up. It goes with the territory.

Then came the pandemic. I left Savannah and came back home last spring, thinking it was as good a time as any to move closer to Mom, anyway. But the job I was anticipating in Tifton just dissolved into the ether with the virus, and the transcription work I’d been doing for years ground to a halt because it largely involved medical professionals that were now too busy on the front lines to tend to their research projects. I started casting around for ways to earn the rent. Then one day Mom asked me to prune the overgrown yews at her front door. Mom and I live in the same apartment complex, where aesthetics management had gone unattended for…let’s just call it a while. It was April. I cut back the yews.

Then I cut back the neighbor’s yews. Then I started weeding because it was late May and that needed doing. Soon the property manager and I came to an agreement. Next thing I knew, I was whacking all the spreading yews back to sticks, cursing the giant liriope and the root sprouts from the Chinese elms, digging out diseased Indian hawthornes and wondering whether to replace them.

And that’s how it started. Let me tell you, I had a vertical learning curve. I knew very little about what I was doing. VERY little. I didn’t even know they were yews; I had to send a picture to my cousin to find out. And selective pruning? What’s that? Why not use hedge clippers? What happens if I cut off this branch? I mean, it’s one thing to cut back your own azaleas; it’s another thing entirely when they’re someone else’s. I felt like I was always on the lookout for the pruning police. Every cut I made was a leap of faith. Still is, really.

And the exotics, good grief. The Taiwanese photinia in the front here is 20 feet tall and just as wide. Of course, I didn’t know they were exotics. If someone had said, ‘Hey, that’s an exotic,’ I would have said, ‘But what does that mean?’

And I was so frustrated that I couldn’t name things. It drove me crazy not to know I was looking at a Chinese elm or a willow oak or viburnum or vetch – or Confederate jasmine, which I misidentified as creeping fig (with great confidence) for months. I called a loquat tree a magnolia (with equal confidence). Couldn’t identify camellias, and I’d grown up with those. Embarrassing! It has taken months to learn enough just not to lose sleep at night, and that’s after hundreds of hours of Googling, YouTubing, and a lot of frantically sought advice from my Georgia Native Plant Society friends, the UGA Extension service, my friend who is the Chief of Forestry and Wildlife at Ft. Stewart, innumerable field guides, and the PictureThis app.

I said before that I would never choose nonnative plants now. So what changed? It just happened, like an impulse. It wasn’t a decision, something I’d settled on. I hadn’t done any particular research. In fact, to be honest, at the time that shift in my thinking came about, I must have just internalized somehow, after pushing back on them day after day, how imports were edging out the natives, making life hard for the local birds and bees and butterflies, and destroying, little by little, what the Unitarian Universalists, whose choir I used to sing in, call the interdependent web of all existence.

Anyway, one day in utter frustration over the giant liriope that had been expanding unchecked for two decades…

…it occurred to me that I could replace all this overgrowth with native plants. Now, understand, I didn’t know the first thing about landscape design, but that didn’t cross my mind. I just called up the property manager and said (authoritatively), “Hey, from now on, whatever we buy has to be a native.”

I totally agree,” he said. “Makes perfect sense.”

Imagine my astonishment. Oh, no, I thought. Now what?! I mean, Google and YouTube are great, but they’re no substitute for experience. The scope of my knowledge was limited to what I’d grown myself. In my mind’s eye, I could see muhly grass and native azaleas and beautyberry in two years – but what could I use for ground cover? What could go in front of these columns? What trees, what flowers, what shrubs? Where? How much sun, how much watering, when and where and how deep to plant? What about mulch?

Desperate for information and direction, I started calling, emailing, peppering people with questions, asking for advice, begging them to come look, to help me identify possibilities. Meanwhile, over the summer, besides freeing the topiary frames…

…I was also doing this…

…assembling cardboard jigsaw puzzles under acres of pine bark mulch. (Yes, that variegated liriope is still there – at the moment.)

But that was then. This is now. I keep telling people I hope this all ends up looking in real life like it does in my imagination.

To put a finer point on it, now, where once were liriope and diseased Indian hawthorne and a proliferation of Chinese elm sprouts are now Virginia sweetspire and muhly grass, native viburnum and beautyberry, rain lilies and this single weeping yaupon. Native fringetrees and Shumard oaks will replace hurricane-damaged Chinese elms. Yellow jessamine, coral honeysuckle, passion flower, and native wisteria have replaced the Confederate jasmine, creeping fig, and English ivy under the freed topiary frames. I’ve added some dwarf wax myrtles, planted cardinal flowers and blue lobelia, put Powderpuff (Mimosa strigillosa) in the island and Christmas fern under the hollies and loquats. I have plans for native azaleas and oak leaf hydrangeas someday. In time, I like to think I’m doing what is described best by Larry Mellichamp and Paula Gross in The Southeast Native Plant Primer (Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, 2020): creating an “island of diversity in a sea of urban uniformity,” square foot by square foot by square foot.

(Enthusiastic thanks to Mary Alice Applegate, Amy Heidt, Heather Brasell, Katherine Melcher, Greg Lewis at Flat Creek Natives, all from GNPS, along with Larry Carlile, Chief of Forestry and Wildlife at Ft. Stewart, and Kelly and Syd Blackmarr, invaluable comrades in my quest to change the world – and how we see it.)

|