|

From the State Board

Gardening – The Perfect Stay-at-Home Activity

Much better than housecleaning or laundry, gardening is the perfect stay-at-home activity in times like these. How many ways to garden are there? Let us count the ways!

- There is the ‘add new plants’ flavor but most seasonal sales got canceled. A few native plant nurseries are still open and you can find them on our website (and then start calling to see who’s open or check for them on Facebook and their website). Perhaps friends are dividing perennials or cleaning out extras. Ask them to leave them where you can come pick them up and offer to bring another plant to leave in return. I’ve been doing this with several folks.

- There is the ‘boy, I’ve been wanting to re-do that area for ages’ flavor and you need only your trusty tools to get to it. You can add plants to it later. Give it a nice layer of untreated mulch or pinestraw to hold it over. The front bed next to my sidewalk was crying for attention; one delivery person told my husband that it looked ‘snake-y’ and that was the final incentive I needed. I replanted a lot of the removed plants into my neighbor’s yard.

- Finally, there is the ‘remove invasive plants from your yard’ flavor. Do you have English ivy, Ligustrum (privet), Japanese honeysuckle, Mahonia, Nandina, or other pesky invaders? My personal war this year is on Youngia japonica, a prolific annual weed that has taken over numerous parts of my woods. I ignored it for several years and that was a mistake. Now I stuff my pockets with it as I walk around (like dandelions, they can still set seed if you drop the pulled-up plant on the ground). See Heather Brasell's timely article later in this newsletter for more on invasive plant control.

I hope you have already taken some time to nurture your native garden a bit during this past month. As stay-at-home recommendations continue into May, I encourage you to keep going or get started if you haven’t. Number 3 is really one that can benefit your local environment by opening up room for more native plants (some even return on their own after smothering plants are removed).

And as always, if you have questions or would like to reach us about other matters, send email to board@gnps.org.

Top photo: Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia). Photo taken at FDR State Park early May 2018. Photo by Ellen Honeycutt.

Chapter News: Redbud

Left: Jess Riddle. Top middle: Jess Riddle signs a copy of his book Georgia’s Mountain Treasures for Lynn Kearns, Redbud Project volunteer liaison to Gainesville Parks and Recreation. Bottom middle: Jess Riddle answers questions with Karen Bird, Redbud Project volunteer sponsor. Right: Jess Riddle among champions in old-growth forest.

North Georgia Forests—Treasure Trove Warrants Protection

Stephen Smith and Margaret Rasmussen

With their great diversity of plants and animals, North Georgia’s rich habitats of old-growth forest ensure the survival of native species plant populations.

As forest ecologist Jess Riddle documented in his Redbud Chapter program, “Where and Why of North Georgia’s Old-Growth Forests,” the need to preserve these natural ecosystems is urgent. Riddle appreciates the work required to protect remaining wild and un-fragmented old-growth forest communities. He knows Georgia’s national forestlands closeup and personal, having hiked Chattahoochee National Forest as a youth and developed his interest in old-growth forests, native flora and champion trees.

Champion trees are the best indicator of forest maturity (succession climax) in the natural ecosystem aging process, with some specimens having lived for several hundred years. When Riddle joined the Georgia ForestWatch (GFW) team in 2001, his sole job was to document old-growth forests in the Chattahoochee National Forest. While he inventoried 7000 acres of old-growth forests on the Chattahoochee River that were vulnerable to being logged by the Forest Service, he nominated over 40 Georgia state champion trees that had survived.

A champion tree is defined as the largest known tree of a particular species in some designated region. Keystone species such as white oak, white pine, pignut hickory, chestnut oak, Fraser magnolia, tulip poplar, hemlock, and pawpaw can affect entire ecosystems simply by performing natural behaviors for survival. The sugar maple tree, for example, has the ability to transfer water through its roots from moist soil to dryer areas, benefiting nearby plants. The canopy of this tree provides cover and habitat for many species of flora and fauna. Insects, which are important to enriching soil, rely on the canopy for preservation of moist soil conditions.

Now as executive director of Georgia ForestWatch, Riddle works to encourage sustainable management practices to protect old-growth forests, champion trees and native flora. After studying ecology at Furman University, he focused on tree climate growth relationships for his masters degree at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, the premier college in the US for science, design, engineering and management of natural resources and the environment.

While GFW has inventoried thousands of acres of old-growth forests, their work accounts for only about one percent of the 867,510 acres of national forestlands in Georgia. Many more areas can be counted in the preservation totals if the public joins in this effort to promote preservation of this treasure trove of habitats for future generations.

As important indicators for conservation, old-growth forests have stable temperatures and relative humidities, species richness and structural complexity where insects and related arthropods reach their highest diversity. Fallen, decomposing trees sustain a web of life that extends from soil-building micro-organisms all the way up the food chain.

Today preservation work is urgent as about 60,000 acres were harvested last year, the most in 10 years. Historically, industrial logging peaked between 1880 and 1930, leaving only about two percent of virgin forest in the Chattahoochee National Forest. Clear cutting was partial in those days, based on timber value and accessibility. Recovery has been slow but steady.

Georgia lost about 100,000 acres of forest between 1990 and 2000, with US National Forests today under continuous pressure to allow lumber companies to harvest these rich natural ecosystems from lumber operations, Georgia ForestWatch (GFW) has made it a priority to preserve, protect and restore as many of the existing old-growth forest communities as possible.

With new technology, forests ecologists can calculate tree height from high above using LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) that uses pulsed laser beams to measure distances to targets. From an aerial view, these numbers can be converted into a 3-D map of the surface terrain. The map shows land and tree heights that can indicate areas where old-growth forest sites exist for study.

Riddle documents his experience and shares his passion for protecting forests and their flora in his book Georgia’s Mountain Treasures: The Unprotected Wildlands of the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forests, published by Georgia ForestWatch (2018). He features 40 unique and special wild areas in North Georgia that warrant protected status from logging, road construction and other management practices that would threaten their ecological integrity. Maps, photographs and scientific biological data of woodland areas and communities encourage the public to seek out rare plants, old-growth trees and historic sites in their communities so they are set aside to insure survival of native species plant communities for future generations.

Contact information:

Jess Riddle, jriddle@gafw.org

81 Crown Mountain Place Building C, Suite 200

Dahlonega, GA 30533, info@gafw.org | 706.867.0051

White Oak candidate for champion tree discovered at Gainesville Mundy Mill subdivision.

Search for Champion Trees

Old-growth forests are not always the only place to search for champion trees. You might find a candidate to register as a champion tree in a subdivision, on a city street, or on a native plant rescue.

To identify a candidate as a state champion species tree, check the criteria of the Georgia’s Champion Tree Program overseen by Georgia Forestry Commission (GFC):

- Must have an erect woody perennial stem, or trunk at least 139.5 inches in circumference when measured 4.5 feet from the ground and at least 13 feet total height with a definitely formed crown of foliage. [This could vary with species]

- Species must be recognized as native or naturalized in the continental United States, as listed in the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture Agricultural Handbook 541.

Happy hunting.

Redbud “Urgent Care” for Pandemic

Worldwide, we suffer in body and mind from the pervasive effects of the coronavirus pandemic, when effects can be alleviated with one readily available remedy: Vitamin N (nature)!

Redbud Project “Urgent Care” is open dawn to dusk at Linwood Nature Preserve, GNPS chapter’s model for mental and physical health in green space. Two miles of eco-friendly trails wind through 30 acres of oak-hickory, prairie and wetland ecosystems. You can fortify your immune systems and take a whack at cabin fever with regular doses of nature among the native trees, shrubs and herbs.

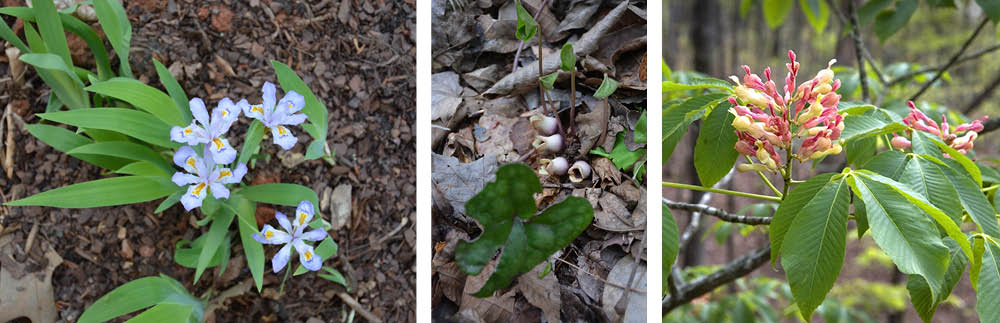

Dwarf crested iris (Iris cristata) hug the hillsides of the prairie paths, heartleaf (Hexastylis arifolia) is among the variety of species that cover the ground, and painted buckeye (Aesculus sylvatica) flourish in a ravine that flows into Linwood Cove of Lake Lanier.

Current scientific studies support the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, who espoused, “If our mind is agitated by passion, emotion or anxiety, the body cannot eliminate all the refuse and toxins that give rise to symptoms which we call disease.”

Scientific research of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that nature may be the pathway to fortify the human immune system and positively affect mental, spiritual and physical health. Because flow of blood to the brain has a physiological effect on the body, time spent in nature provides protection against diseases—depression, diabetes, obesity, ADHD, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and, assuredly, infection and virus.

Flame azalea (R. calendulaceum) spread out across the oak hickory forest while jack-in-the-pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) spread across the wetlands, and a redbud (Cercis canadensis) arches near the deck.

Linwood Nature Preserve is located in the heart of Gainesville, easily accessed by foot, car and public transit. The two-mile trail system is constructed by the bench hill method with minimal elevation and packed surfaces for easy access. Benches and decks throughout the preserve provide areas for rest, meditation and access to nature.

Linwood Nature Preserve’s natural ecosystems harbor a treasure trove of native plants indigenous to the Gainesville Ridges.

Remi and Trail Steward Sally Reynolds.

Trail Steward Sally Reynolds walks the Linwood trails three or more times a week for 60 to 90 minutes with her three-legged dog Remi for her mental and physical health and to keep his muscles strong. A cardiology nurse, Reynolds supports the scientific studies that suggest accessibility to natural areas may be vital for mental health of our rapidly urbanizing world.

Japanese doctors who have studied the effects of “Vitamin N” on blood pressure and heart rate prescribe shinrin yoku—forest bathing, 20 minutes a day. Redbud Project “Urgent Care” at Linwood Nature Preserve for Rx health and wellness is open seven days a week dawn to dusk.

No appointments required — walk-ins welcome at the Redbud Project Chapter “Urgent Care!”

Linwood Nature Preserve

415 Linwood Drive

Gainesville, Georgia

Plant Spotlight: Crossvine

Ellen Honeycutt

Crossvine (Bignonia capreolata) uses small clinging disk pads to climb high into trees. The brightly colored, tubular flowers attract hummingbirds.

Native vines don’t always get the garden attention they deserve. Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens) gets much of the positive attention while Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans) battle for the lowest spot in the line-up. One of my favorite under-appreciated vines is crossvine (Bignonia capreolata), an evergreen vine that is just finishing up its blooming season here in the Piedmont. Often found high up in the trees, fallen blossoms on the ground are one way we notice it. Visitors to Arabia Mountain, Panola Mountain, and other granite outcrops might also find it growing in the thin soils that border them, scrambling over stunted shrubs and trees.

A key to understanding vines and how we might use them in the landscape is to understand their attachment mechanism. I wrote a blog several years ago about that (you can find it here). Crossvine has clinging disks that help it adhere to tree bark and flat structures like wooden fences. The adhesion is not so strong that it damages the structure. It also may attach to slim branches and wire fences with tendrils.

Vines are scramblers, and crossvine is no exception; we often find it on rescues as just a couple of oppositely-arranged leaflets poking through the leaf litter in the winter (the leaves themselves are compound, but often only two leaflets show). Pull away the litter and you’ll find it is not a single plant but the opportunistic upward branch of a vine. Like many vines, a small piece can often regenerate into a new plant.

Crossvine is popular with hummingbirds, evergreen, and a spring bloomer — three characteristics that should endear it to more gardeners looking for a vine. With a range that spans the entire state, crossvine is one that we all can consider. Brightly colored cultivars such as ‘Tangerine Beauty’ and 'Atrosanguinea' are sometimes sold in better nurseries or ask a friend for a start. The common name, crossvine, is derived from the shape of the pith in the vine’s stem when viewed in cross-section, but I’ve never found one big enough that I was willing to cut it open to see that view.

Crossvine (Bignonia capreolata) cultivar and winter foliage.

Dealing With Invasive Species

Heather Brasell

I’m seeing the spring resurgence of invasive plants everywhere I look. In this COVID-19 world, I’ve been reflecting on the botanical pandemics, epidemics, and invasions that surround us. It seems to me that the difference between them is really just one of invasions on different scales. Pandemics are global infections of pathogens invading individual organisms. Epidemics are similar events on a more limited geographic range. Invasions usually apply to non-native species invading an ecosystem.

English ivy (Hedera helix) is a highly aggressive invasive that can easily be prevented from climbing and choking trees, although elimination often takes sustained effort.

Based on a brief search to satisfy my curiosity, the only botanical disease described as a pandemic I could find is chestnut blight, but Dutch elm disease, emerald ash borer and laurel wilt are described as having caused epidemics. In south Georgia, emerald ash borer hasn’t yet reached us, but we have already lost nearly all of our red bays to laurel wilt disease. Invasions are much more common. It seems to be shaping up to be a “good” year for Japanese climbing fern (Lygodium japonicum) and sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata) in the woods, and annual trampweed (Facilis retusa) and field burweed (Soliva sessilis) in my yards. I’ve been mowing infestations of annual ryegrass to prevent it seeding and spraying it or hand pulling it in sites I can’t mow.

We have been learning a lot over the last couple of months about how to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19. We can apply many of the same practices to our management of invasive plant species – as well as transmissible botanical diseases. Perhaps our new awareness and concern about disease transmission among humans will make it more possible and more palatable to take appropriate actions in the botanical world.

First, prevention is easier than mitigation. For instance, Georgia is one of only four states that doesn’t have a noxious plant list. Plant nurseries sell plants that are invasive. Then landowners spend millions of dollars each year to try to eradicate the ones that have escaped.

Preventive hygiene limits the scope of invasions. There’s a reason why so many invasive plants occur in disturbed areas and along roads and woods trails. The seeds or propagation material are transported by human activity. To prevent spread of invasive plants, I mow all trails on my property so seeds of invasive plants don’t have time to mature and get spread by passing vehicles. We regularly wash down all equipment that has been operating in areas where invasive plants have produced mature seeds. When Japanese climbing fern spores are mature (from September to spring germination), we avoid using any equipment in sites with known infestations. We also avoid walking near the plants to prevent carrying them on our clothes.

An untended curbside location is quickly overgrown with invasives, here including mimosa (Albizia julibrissin), japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), glossy privet (Ligustrum lucidum), chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense), greater periwinkle (Vinca major), and everlasting peavine (Lathyrus latifolius). Even a hardy native like Virgina creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) is barely surviving here.

Identification and early detection are critical. Field botanists like GNPS members can make a huge impact by recognizing and reporting invasive plants, particularly in places that are off the beaten path. I am amazed at how few of the invasive plant species listed by Georgia Exotic Plant Pest Council (GA-EPPC) have been reported for my rural county of Berrien. We can all take photos in the field and report occurrences of invasive plants on the GA-EPPC site. We need data on the range and occurrence of invasive species to establish the need for controlling them and to justify the expense.

Introduce control measures sooner rather than later. It’s a lot easier to control an outbreak early and aggressively rather than wait until the invasion spreads. Controlling individual plants or small areas is not only less time consuming and less costly, but also minimizes collateral damage to native species in the same community. Aggressive treatment is often needed to make sure that no seeds have a chance to mature and expand the invasion. Several of the invasive plants I deal with, including beefsteak and hairy indigo (Indigofera hirsuta), have several generations of seed production over a growing season. Infestations of these species need multiple treatments each year to prevent seeds from maturing.

Monitoring for outbreaks is essential. You are extremely unlikely to eradicate an infestation of invasive plant species with a single treatment. The second wave of invasion is likely to impact a much larger range that the initial invasion. Depending on the species, I monitor treated sites frequently for at least three years, then periodically after that. I also monitor trails and areas where contractors have been using equipment – logging, road repair, dam construction.

I have had a lot of invasive plant species on my property. When I first started trying to get rid of them, my approach was rather haphazard. It seemed hard to make headway. Over the years, I’ve developed a more systematic strategy. I've learned not to bite off more than I can chew. Each year, I tackle a new area based on priorities of the habitat (native plants) and the aggressiveness of the invasive species.The new area is manageable – I expect to be able to eliminate all (I hope) of the plants in the site, monitor frequently (about monthly) and re-treat as necessary. Then I monitor systematically for the next three years, re-treat if needed, then monitor periodically after that. By treating a new area each year, I can keep track of the progress I’m making and make sure I don’t lose the war because I defaulted on the second wave of invasion.

Of course, the thing we all do well is promote native plants.

|