Happy New Year!

After adopting new bylaws in November 2019 to restructure GNPS into a more effective organization (summary of changes here), we were excited to embark on a statewide expansion of chapters under guidance and policy set by the new state-level board of directors and committees. However, we were not immune to the challenges that 2020 brought to the world. Shortly after our February 29th Symposium, it became clear that our robust plans for new chapters would have to wait until it was safe to resume in-person gatherings.

Luckily, much of our formative state-level policy work, an important part of the change, was able to continue through remote meetings of the committees — Conservation, Education, Finance, Audit, Governance, and Member/Chapter Support. All committees made good progress in creating policies and procedures to guide the organization at the state level. Committees also are reviewing and revising existing programs GNPS programs such as Habitat Certification, Plant Rescue, and Site Restoration so that new chapters can quickly and effectively implement these programs at their local level.

In 2021, the state board of directors will continue to formulate strategic initiatives across the state. Committees will continue to translate that strategic plan into educational tools and activities to help chapters engage members. Chapters will continue to work in their local communities carrying out the mission to teach more Georgians that using native plants and safeguarding existing native plant habitat through our conservation policies are important efforts.

As the year concludes, here we provide a summary of where GNPS is now and some of what we look forward to next year.

Chapter Status

- Chapters will lead local programs like regular meetings, workshops, Habitat Certification, plant rescue, site restoration, local propagation, and working with local partners such as cities, counties, and like-minded groups.

- Members may currently affiliate with any of 3 existing chapters: West Georgia, Coastal Plain, or Redbud Project (Gainesville area).

- Areas where chapters were beginning to form and which we hope will move forward in 2021: Atlanta, North Metro Atlanta, Macon, Augusta, Athens. Email us at chapters@gnps.org to get more involved in forming chapters.

Membership

We end the year with 1,150 memberships, a 13% increase over the beginning of 2020. Each of our 3 chapters has approximately 100 memberships, so the bulk of our members (695) are in areas where those new chapters need to form so they can have access to local programs and volunteer opportunities.

New Items

- New scholarships were funded to support the Native Plant Certificate program administered by the State Botanical Garden. Two annual scholarships will be funded: one for a Piedmont resident, one for a Coastal Plain resident.

- Stone Mountain Propagation Project will shift away from growing plants solely for Atlanta area plant sales and focus on growing local ecotypes that are not readily available but deserve wider landscape use. SMPP also will support chapter propagation efforts and cultivate a broader educational partnership with Stone Mountain Park.

Continuing Programs

- Symposium: The 2021 Symposium will be held virtually across two sessions on February 27 and 28 (2 hours each day). GNPS will partner with Georgia Audubon to execute this program entitled Georgia’s Wildlife from the Ground Up: Why Native Plants & Places Are Essential

- Newsletters/Website Communications will remain at the state level for 2021, although local chapters may also have newsletters and individual websites.

Society Financials

As of November 30, 2020, our total income was $39,534 with total expenses of $36,282. In 2020, membership and program income were our primary sources of income while our February 2020 Symposium and administrative expenses were our largest costs. Our reserves of just over $200K are safely invested in anticipation of future statewide growth and the support that our chapters may need.

Our Treasurer, the Finance Committee, and the State Board made several key decisions in 2020 that resulted in 1) savings on insurance while also improving our coverage; 2) improved investment income; 3) savings on our storage unit (moved to a cheaper location); and 4) savings on website services.

State Board

The following new board members are joining in 2021: Mary Lillian Walker, Kevin Burke, and Carling Kirk. We wish to thank our departing members: Leslie Edwards, Marc LaFountain, and Henning von Schmeling.

Thank you for sticking with us through this challenging year of 2020. We hope you will renew your membership in 2021 and continue your support of our mission and the growth of GNPS. For those of you with an expiring membership, you should have already received an email reminder; we encourage you to renew. Reach out to the board with any questions or to volunteer: board@gnps.org.

Top photo: Half Moon Lake, Okefenokee swamp in winter. Photo by Tom Collins.

Fringetree (Chionanthus virginicus) is the 2021 GNPS Plant of the Year

Valerie Boss

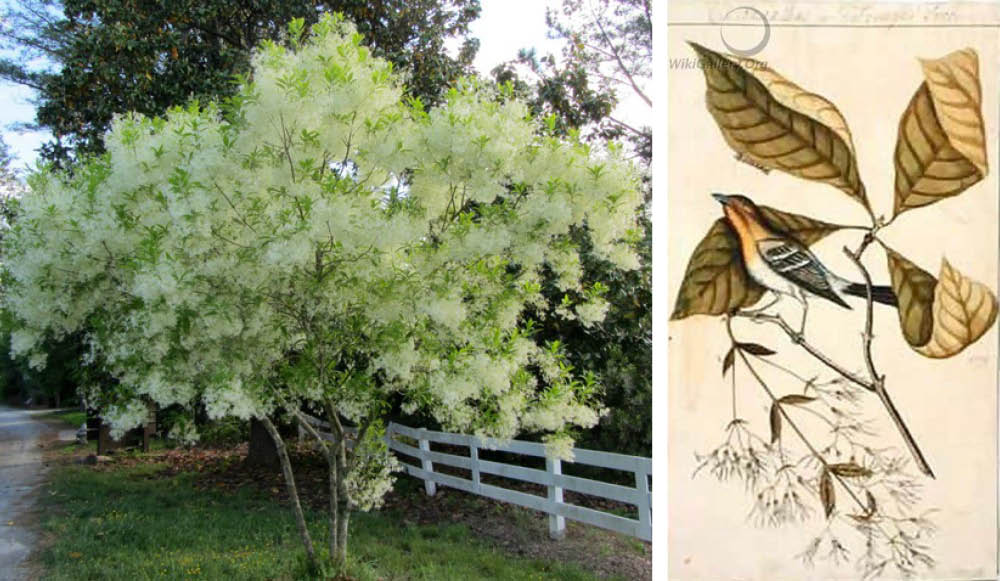

Left: Fringetree in full bloom (photo by Ellen Honeycutt). Right: Willam Bartram’s painting of fringetree (http://www.wikigallery.org/).

This year’s Plant of the Year (POY) is fringetree (Chionanthus virginicus). Also known as white fringe tree, old man’s beard, or grancy graybeard, this small flowering tree grows along the east coast from New York to Florida and across the south to Texas. It was first collected as a botanical specimen in 1678 by John Banister, a young clergyman with an interest in natural history. He was appointed by the Lord Bishop of London to both minister to the colony of Virginia and explore its native flora and fauna, hence the species name virginicus. Botanist John Bartram identified the plant in the 1730s during travels in the northeast. He and his son, William, a naturalist and illustrator, later collected the species further south during a 1765-66 expedition across the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. The image above depicts a lovely oil painting of fringetree created by William Bartram (a wiki watermark in the photo could not be removed for copyright reasons). Thomas Jefferson, a contemporary of John Bartram, was notably fond of fringetree. During his residence in London, Jefferson wrote to Bartram, requesting seeds to share with friends in France. A legacy of their collecting remains. Fringetree still grows at both Jefferson’s Virginia home, Monticello, and John Bartram’s garden in Philadelphia.

In the wild, fringetree can be found in a variety of environments, including moist, open woods, pine scrubs, and granite outcrops. It can be single or multi-trunked, with pale gray-brown bark, and an open structure. A slow-growing species, it can reach 10 to 30 feet in height and can achieve a crown spread of up to 20 feet. Its deciduous leaves are simple and opposite. They are elliptical in shape, up to 6” long, with smooth edges, glossy tops and pubescent undersides. Dark green in color, they turn yellow in the autumn.

Terminal panicles festoon spring branches (photo by Ellen Honeycutt).

Fringetree is best recognized for its eye-catching spring blooms, shown above. It is very late to leaf out in spring and may appear dead. But as the leaves begin to make an appearance, the tree blooms — and what a show! Individual flowers are long, white, and fine, forming copious clusters of terminal aromatic panicles. The genus name Chionanthus, meaning snow and flower, refers to the blooms.

Fringetree is most commonly planted for its ornamental appeal. The tree is well-suited to landscape borders, growing in sun or part shade and many soil types. It is a fairly non-descript tree during most of the year, but it presents a striking point of visual interest in the spring. The species has separate male and female plants, both of which exhibit the characteristic flowers. If both sexes are present, the female can produce clusters of blue-black drupes, about ½ inch long. These fruits feed the birds and are an additional source of visual appeal in the garden. Insects also benefit from fringetree. It is host to several species of native sphinx moths, including the rustic sphinx moth (Manduca rustica). Historically, fringetree also had an additional use as a medicine. A tincture of the bark was taken to stimulate the liver.

A member of the olive family, fringetree is related to several genera found in Georgia, including native ash (Fraxinus) and devilwood (Osmanthus), as well as the dread invader privet (Ligustrum). Fringetree is resistant to most pests but is susceptible to emerald ash borer, which decimates ash trees with amazing speed and efficiency. Fortunately, fringetree has some resistance to the pest. Trees are weakened by the borer and often lose limbs, but they do not always die when infested. Because of the rate at which the emerald ash borer is currently spreading, it is very important not to buy fringetree plants from states where an infestation has been reported, or to transplant even healthy specimens from infested areas. In Georgia, infestations are prevalent in the northern half of the state, especially metro Atlanta. Fortunately, our beautiful POY2021 can be grown from seed.

Emerald Ash Borer, a Highly Efficient Killer

Left: Adult emerald ash borer (photo by David Cappaert, Bugwood.org). Right: Larvae and tunnels (photo by David Cappaert, Bugwood.org).

Here’s a fact that most people don’t know: Georgia is under statewide quarantine for the emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis). As of 2017, it is illegal to transport non-heat-treated ash wood, ash trees, or any non-coniferous firewood from infested areas throughout the state of GA. Why? What is emerald ash borer, why is it bad, and how did it get to Georgia?

Emerald ash borer is an iridescent green beetle native to eastern Russia and parts of Asia. It infests and kills ash trees. It was first detected in North America in 2002, in trees dying in Detroit, Michigan and nearby Windsor, Ontario. Michigan is the most likely site of introduction to North America, probably in the 1990s, via packing material, such as crates or pallets. Despite attempts to quarantine the pest, by 2004 the borer had made its way into forests and urban areas in Michigan, Indiana, and Ohio, killing 15 million trees. As of 2019, emerald ash borer has become rampant in at least 35 states, plus the District of Columbia, and 5 Canadian provinces. Tens of millions of ash trees have died.

This invasive pest is an extraordinarily rapid killer. Infested trees last only 1-3 years. The adult beetle lays eggs in the bark of an ash tree (even a perfectly healthy one), and a few weeks later the larvae appear. Larvae tunnel extensively through the phloem and cambium (photo below, right), overwintering in the sapwood or bark either as larvae or prepupae. Following pupation, adult beetles emerge in the spring and spread to other trees, leaving distinctive D-shaped exit holes (below, left). The larval stage is the one that is lethal, as extensive larval tunneling effectively girdles the host tree, starving and dehydrating it.

Emerald ash borer was first reported in Georgia in 2013. The northern half of the state, including metro Atlanta, has been heavily hit since then. The photo on the right below was taken recently in DeKalb County. It shows emerald ash borer tunneling in a dead tree at Ira B. Melton Park, where almost every mature green ash succumbed to infestation in 2014-16.

Left: D-shaped exit hole (photo by William Clesla, Bugwood.org). Right: Dead ash, DeKalb County (photo by Valerie Boss).

At first, ash (genus Fraxinus), was thought to be the only olive family (Oleaceae) branch susceptible to the emerald ash borer. Sadly, in 2014, our 2021 Plant of the Year, fringetree, emerged as a second susceptible genus. Fortunately, fringetree has some resistance to emerald ash borer infestation. Individual specimens often lose limbs, but do not necessarily die when infested. Older fringetrees and those that have been stressed by drought or other factors seem to be most susceptible. Olive trees (Olea spp.) can also support the ash borer’s life cycle in the laboratory, although that finding has not been reported in nature. Hopefully, host-switching from ash to olives will not occur, as the economic price would be devastating. The emerald ash borer is spreading in Europe, as well as North America, and olives are an important crop worldwide.

Symptoms of emerald ash borer infestation on ash trees or fringetrees include yellowing leaves, a thinning crown, and D-shaped holes in the trunk. An arborist can determine whether to take an infested tree down and properly dispose of the wood, or try to save it. Treatment typically involves root injection with systemic pesticides. (Pesticides come with their own negative issues, and effects on pollinators should be considered). Emerald ash borer infestations of any tree should be reported, either by contacting the county extension office, or by emailing the Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health at: bugwood@uga.edu.

What can you do to prevent the spread of emerald ash borer? First and foremost, do not transport ash trees, fringetrees, or any type of firewood from one area to another. Infested firewood is a major route for emerald ash borer dispersion. For more information on this disastrous pest, go to the Georgia Invasive Species Task Force or the Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences at the University of Florida.

Cipollini, D. Rigsby, C.M., and Peterson, D.L. 2017. Feeding and development of emerald ash borer (Coleoptera: Buprestidae) on cultivated olive, Olea europaea. J. Econ. Entomol. Aug1;110 (4):1935-1937.

Ellison, E.A., Peterson, D.L. and Cipollini, D. 2020. The fate of ornamental white fringetree through the invasion wave of emerald ash borer and implications for novel host use by this beetle. Env. Entomol. 49(2):489-495.

Haack, R.A., Baranchikov, Y., Bauer, L.S., and Poland, T.M. 2015. Chapter 1: Emerald Ash Borer Biology and Invasion History. US Forest Service. https://www.fs.fed.us/nrs/pubs/jrnl/2015/nrs_2015_haack_001.pdf

Poland, T.M., and D.G. McCullough. 2006. Emerald ash borer: invasion of the urban forest and the threat to North America's ash resource (https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/15034). Journal of Forestry 104(3):118-124.

Chapter News: Coastal Plain

Heather Brasell, CPC President

Each chapter of GNPS has its own character, depending on geography, ecoregion, distribution and interest of members. The Coastal Plain Chapter of GNPS (CPC) currently includes the entire Coastal Plain ecoregion--over half the state--and members are scattered thinly over this area. As a result, our main projects using native plants are for habitat improvement and educational purposes. Thus they have taken the form of small local projects rather than developing a single site. Some of these projects were featured in the October issue of NativeSCAPE.

One of the other features of the CPC activities is the commitment to conservation practices on public land--protecting existing natural ecosystems, restoring sites that have degraded plant diversity, and converting disturbed sites to communities of native plants. Amy Heidt is Chairperson of the GNPS Conservation Committee, with Eamonn Leonard and Heather Brasell also serving on the committee. Amy is also a botanical guardian for an endangered plant species. Eamonn Leonard is not only biologist with DNR, but also coordinates the Coastal Georgia Center for Invasive Species Management Area and is Board Chairman for Coastal Wildscapes, one of our partner organizations. Eamonn, Amy, Karan Rawlins, Paul Sumner, and Heather Brasell are active members of Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance, which is another of our partner organizations. On the coast, Gail Farley, Elizabeth and Barrett King are volunteers on a conservation project at Crooked River State Park. Beth Grant coordinates a group of enthusiastic volunteers in Thomasville and surrounding areas. She was responsible for protecting Lost Forest area next to Thomasville airport, and for developing Cherokee Lake Pollinator Garden. She was also instrumental in saving of Wolf Creek Trout Lily Preserve. She leads field trips to these and other botanically interesting sites in the region. In this issue of NativeSCAPE we will focus on some of these efforts, including collaboration with partner organizations.

Threatened and Endangered Plants

CPC members are very active in collaborating with partner organizations in the Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance. Botanists throughout the state coordinate to identify populations of threatened and endangered plant species. Rare plants are often assigned a botanical guardian. Amy Heidt is the botanical guardian for Isoetes junciformis (rush quillwort). Once a population is identified, it is regularly monitored. In particular, botanists hope to see increased density and distribution as they implement appropriate remedial habitat management practices, such as removing competition, using prescribed fire, and using exclusion cages to prevent herbivory. Several CPC members are volunteers for monitoring these types of populations.

In addition, plant seeds and tissue are collected for seed banks, genetic storage, and also for propagation in controlled nursery-like conditions. Of course, they use ethical collection processes, collecting no more than 10% of available plant material at any site. In fall 2020, Lisa Kruse, biologist with DNR, asked us to collect seed from known locations of Macranthera flammeum (hummingbird flower) in south Georgia. Ron Determann, retired from Atlanta Botanical Garden, joined Amy, Heather and John Cox to search one of the sites. No plants were found at the site this season, but there is hope for next season as they bloom biennially. Hummingbird flower is semi-parasitic and prefers roots of Liriodendron tulipifera (yellow poplar). We will pot seedlings of yellow poplar to help Ron propagate seeds – once they are located.

John Cox, Amy Heidt, and Ron Determann searching for hummingbird flower.

Once plants have been propagated, they are “outplanted” at protected sites close to the collection site. In restoration projects, it is important to use local ecotypes to avoid altering genetic integrity at the site. For several years, CPC volunteers have been propagating various species of Sarracenia (pitcher plants) for outplanting into state parks and DNR sites in south Georgia. One of their projects was included in a previous issue of NativeSCAPE.

In south Georgia, land management practices such as logging, firebreaks, solar farms, road development, and mining may severely disturb sites occupied by rare plants. On one of these sites, the property owner collaborated with DNR biologists to rescue an extensive population of Sarracenia species ahead of major disturbance. Eammon Leonard, Amy, Paul, and Heather helped rescue about 400 plants. Most were potted in the field to maximize survival. Plants will be cared for by CPC volunteers until they can be outplanted next spring. Some will go to remediate the same site; most will be outplanted on protected public property.

Eamonn Leonard lifting pitcher plants for rescue; Amy Heidt potting the pitcher plains on the site where they were rescued.

Documenting Diversity and Distribution of Native Plants

Native plants in rural counties are often undercollected so they are underreported on distribution maps and underrepresented in herbaria voucher specimens. These reference data are valuable in tracking movement of species as a result of climate change and invasion of introduced species. They can also provide sources of material for genetics studies. There are two ways to fill these gaps: inventory all plants in a specific area or search lots of suitable habitats for a specific species of interest.

Early in 2020, Linda Chafin, botanist at UGA and the Georgia State Botanical Garden asked Heather Brasell to collect voucher specimens from her property in undercollected Berrien County. By the end of the year, Heather had collected over 400 specimens and taken photos of diagnostic characteristics to help in identification. Quite a few of these are new reports for the county. At one small site, she found at least 10 fern species.

Linda Chafin and Heather Brasell checking out sites where voucher specimens were collected.

As botanists and plant enthusiasts explore native communities, they also find populations of plant species outside the known range for the species. In summer 2019, we found a spider lily we didn’t recognize. Karan Rawlins distributed seeds and plants to four partner organizations for identification. After these plants flowered in summer 2020, they were identified by Henning von Schmeling as Hymenocallis duvalensis (Dixie spider lily). Henning asked us to check on sites identified in south Georgia from two 40-yr-old voucher specimens. The spider lily still grew on one of the sites on a riverine floodplain, so we decided to explore other accessible locations where there were bridges over rivers. CPC members Heather Brasell, Amy Heidt, and Paul Sumner found populations of mostly Hymenocallis duvalensis at several of these locations on both the Alapaha and Willacoochee Rivers. At one site on a tributary of Little River, we also found H. occidentalis (hammock spider lily), which has leaves that are more narrow and less fleshy.

Hymenocallis duvalensis flower and leaves; Hymenocallis occidentalis leaves.

Increasing Availability of Native Plants for Planting

One of the factors limiting the use of native plants in landscaping is the lack of available plants. UGA collaborated with plant nurseries to select four Pollinator Plants of the Year for promotion in plant sales in 2021. The plants of the Year for 2021 are Conradina canescens (spring bloomer), Clethra alnifolia (summer bloomer), Solidago petiolaris (fall bloomer), and Asclepias tuberosa (Georgia native). Heather Alley, horticulturist for State Botanical Garden, provided seeds of Solidago petiolaris (downy goldenrod), and they are currently being propagated by Greg Lewis, Amy Heidt, and Heather Brasell.

CPC members have become more active in propagating a wide range of species of native plants for sale to homeowners and in donating to community garden projects, understory and restoration/meadow projects. Amy Heidt and Paul Sumner are in charge of propagation and plant sales and do the lion’s share of the work. Other members help out by collecting seed and with various propagation tasks. Last year we had over 50 species of native plants for sale and we will have even more species available for sales in 2021.

Kalyn Potts collecting seed from native grasses; Propagating seeds for plant sales and community projects.

Native Groundcover Restoration

Eamonn Leonard, CPC Treasurer

Eamonn Leonard, biologist with Georgia DNR, has been working on several projects focused on native groundcover restoration. This work is based out of the Altama Plantation Wildlife Management Area in Glynn County on the coast. This ~4,000 acre property was acquired by the state of Georgia in 2015 and comprises two historic rice plantations (Hopeton and Altama Plantations) and was acquired as part of Georgia DNR's initiative to conserve lands within the Altamaha River Corridor. The Altamaha Conservation Corridor has been made possible by collaboration among many conservation partners. Each property is in various stages of restoration through the use of prescribed fire, timber thinning, and planting the appropriate overstory species (mainly longleaf pine). The composition of the groundcover varies widely from stand to stand and among properties. All these factors are interrelated and affect the ability to manage these properties for wildlife habitat. A diverse groundcover with desirable native species is critical for providing habitat for many of the target wildlife species including bobwhite quail, gopher tortoises, indigo snakes, turkey and the red cockaded woodpecker, to name a few. The presence of wiregrass and other warm season native bunch grass species is required as food source, ground cover for ground nesters, and fuel to help return fire to these systems.

On Altama Plantation WMA several old cultivated fields and a former airstrip were suitable for growing desirable native groundcover species. About 11 acres was planted in September 2020 with about 58,000 wiregrass plugs. These areas will be managed with prescribed fire in the growing season since this is a requirement for wiregrass to produce viable seed. These seeds will then be harvested and dispersed to properties within the Altamaha Conservation Corridor that lack sufficient wiregrass cover.

Additionally, Georgia DNR is converting a former 5-acre vegetable garden into a native groundcover production nursery. Over 40 species of native forbs, legumes, and grasses are being collected to be grown in rows in this location. Georgia DNR is collecting seed for the project from within the South Atlantic Coastal Plain plant transfer zone with an effort to prioritize collection within the Altamaha Conservation Corridor. With funds from private donations, a shade house is being constructed as propagation area for the target species and new irrigation lines will be installed. The seed collected will first be grown up in plugs and then transplanted into the planting rows. Each species will be planted out separately to ensure ease of future seed harvest. The list of species was chosen in order to have flowering throughout the growing season, species that provide cover and food for quail, cover and food for gopher tortoises, and nectar and host material for pollinators. Once established, seeds from each species will be harvested and disbursed to Georgia DNR and partner conservation properties in the Altamaha Conservation Corridor that have low groundcover diversity.

Centrosema virginana (butterfly pea), Coreopsis species and Eragrostis spectabilis (purple love grass), Liatris elegans (elegant blazing star), Asclepias tuberosa (butterfly weed), and milkweed seed.

Plant Spotlight: Wax myrtle (Morella cerifera)

Ellen Honeycutt

Wax myrtle (Morella cerifera)

When you go out the door on a chilly January day, what is the first thing you look for? For me, it’s a bit of something green. I need to see some confirmation that life is still there. While I love the look of bare deciduous tree branches, I need the green! Therefore, when I write Plant Spotlight features in the winter, I try to pick something evergreen to discuss. Last January was resurrection fern and the one before that was Christmas fern. This time, it’s wax myrtle (Morella cerifera).

Many years ago, in 2002, this native shrub was chosen as the GNPS Plant of the Year. That was before our t-shirt program, by the way, so you won’t see anyone walking around in a wax myrtle shirt. It was selected for good reasons: this shrub is native to the Coastal Plain and Southern Piedmont and is adaptable to a wide variety of growing conditions including damp to dry soil and from sun to shade. It tolerates poor soil amazingly well, due to its ability to fix nitrogen through root nodules. The wax myrtle is even accepting of salt spray, making it suitable for beachside plantings.

Flowers are borne on separate male and female plants (so plan to get more than one); the tiny female flowers turn into equally tiny fruits: only about 1/8 inch in diameter, they are an attractive bluish-white and are relished by many songbird species, including the bluebird, tree swallow, catbird, myrtle warbler (also known as the yellow-rumped warbler), and the Georgia State Bird, the brown thrasher.

The evergreen leaves add color to the landscape and shelter for birds. The plant tolerates pruning, allowing it to function as a hedge if needed. Dwarf varieties have been cultivated by nurserymen for smaller yards: look for ‘Don’s Dwarf’ and ‘Suwannee Elf’ among others. If you’re using a straight species plant, allow for a size of 15-25 feet at maturity.

Fruits and flower of Wax myrtle (Morella cerifera).

|