Rebecca Byrd of the Georgia DNR and Amy Heidt, GNPS set out milkweed at General Coffee State Park

The clod of potting soil in a state park employee’s hand is dusted with fragile green leaves. When it is planted into the ground, this seedling will disappear amid grasses and other plants. But a lot of hopes ride on this bit of greenery and more like it — six years and more of advocacy, fund raising, seed collecting and greenhouse growing.

It was just six years ago that Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College found itself in possession of a pitcher plant bog, 8.74 acres of land where some of Georgia’s most unusual plants have grown for decades. Seven species of the insect-eating pitcher plants grow in the state.

All seven are protected, due to widespread loss of habitat, and at least one is endangered. They are among the most unusual plants in the world.

Ben Mills of Fitzgerald had put the property on the market, but when approached by a group of botanists, biologists and native plant lovers, he agreed to donate half his asking price, if the group could come up with the rest. They did, and the bog was then turned over to the care of the ABAC Foundation to be used as a living lab for biology and natural resource management students.

This year, thanks to members of the Coastal Plain Chapter of the Georgia Native Plant Society, ABAC, employees of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources’ non-game and state parks divisions and the University of Georgia and private landowners, the ABAC bog has contributed to an effort to establish new bogs in four state parks: General Coffee near Douglas, Little Ocmulgee near McRae, Reed Bingham near Adel and Laura S. Walker near Waycross.

Georgia’s state parks are attempting to return native plants to their natural “homes” within the parks. The parks are also engaged in a related federal effort to plant native milkweed for monarch butterflies and other pollinators, including bees. Pollinator gardens have now been established in most of Georgia’s state parks.

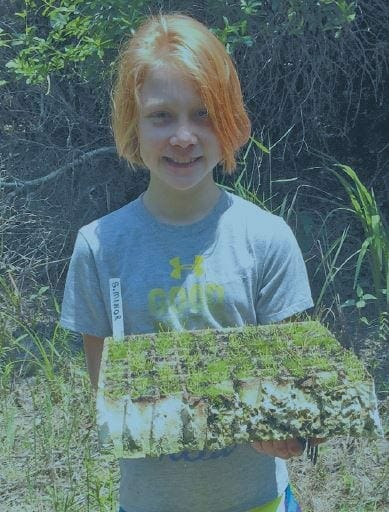

Millie Davidson with Pitcher Plant Seedlings

“We have been working on habitat restoration statewide,” says Lisa Kruse, a rare plant botanist with the non-game division of the DNR. “Certain parks have high priority rare habitats.” These would include parks with wetland habitats like bogs, which are fast disappearing from the Georgia landscape.

The non-game section of DNR works in partnership with the state parks to help with park management. “State parks don’t have a lot of funding for natural resource development,” Kruse points out. The work to restore native habitats has several aspects, including, in South Georgia, prescribed burns. These are critical in the coastal plain where plants and wildlife evolved under conditions of frequent, low-intensity fires (caused by lightning or drought) that periodically burned off understory plants. With modern fire prevention on wild lands, such naturally caused fires have become rare.

Prescribed burns benefit longleaf pines, pitcher plants, gopher tortoises and indigo snakes, among others, all dependent on sunny, open grasslands for survival. Many of these species are now endangered. Other aspects of habitat restoration include getting rid of invasive, non-native plants (such as mimosa trees, Chinese wisteria, Chinese privet, chinaberry, water hyacinth and kudzu) and removing hardwoods where the canopy is too crowded to let in enough sunlight. It’s a lot of work, but Kruse says, “We have good networks of partners, and it’s a lot of fun, too. I’m always learning new things.”

The prescribed burn program was started 10 years ago. “We have made significant progress toward restoration,” Kruse said. “It’s time to put native plants back in place.” The chain of events that led to the recent plantings began with a federal grant through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to the Atlanta Botanical Garden to provide milkweed plants to restore to its native habitats this species vital to monarch butterflies, honey bees and other pollinating insects. “They couldn’t find a source of native, locally grown milkweed,” Kruse says. Commercial varieties would not do.

“They really needed seed collected from Georgia habitats. This is incredibly local, which is really exciting.” To fulfill its obligation, the botanical garden collected the seeds in the wild and hundreds of the seedlings they grew were planted in three state parks in South Georgia.

Sim Davidson, resource manager for the Southern region of Georgia State Parks, received an email from biologist Nathan Klaus about the availability of milkweed for planting in state parks. He and Kruse discussed suitable locations for planting in the region and settled on three, General Coffee, Reed Bingham and Laura S. Walker. And Kruse contacted her friend Karan Rawlins of Tifton. Rawlins is a biologist with the University of Georgia’s Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health (also called the Bugwood Network). With the involvement of Rawlins and Amy Heidt, president of the Coastal Plain Chapter of the Georgia Native Plant Society, the scope of the project expanded.

Rawlins is also a member of the Coastal Plain Chapter of the GNPS, an organization that supports the conservation of Georgia’s native plants. The CPC had pitcher plants in need of homes. “I do a lot of seed collecting and work to develop relationships with local landowners who give me permission to collect seed from their property,” Rawlins explains. All collecting is done using Georgia DNR-recommended techniques designed to protect the parent plants so they will remain healthy and unaffected. The DNR must also approve ahead of time where seed will be planted, Rawlins says.

With ABAC’s permission, Rawlins collected the seeds of Sarracenia flava, commonly called yellow trumpets, and Sarracenia minor, or hooded pitcher plants, from the Turner County bog. In her greenhouse, Amy Heidt grew seedlings from pitcher plant seeds from a bog on her property. “I had first gotten interested in growing native plants in my own landscape,” Heidt says. Her interest led to her involvement with the GNPS and the local chapter when it was formed three or four years ago to promote awareness and use of Georgia’s wonderful native plants in this area.

“They offered to donate pitcher plants” to the three parks, Davidson says of Rawlins and Heidt. The proposal was a natural fit with DNR plans. Davidson also requested some of the pitchers for Little Ocmulgee State Park, where he is based. Pitcher plants had previously grown in a bog in the park and he hopes to reestablish them.

Kruse, Davidson, Rawlins, Heidt and others met with park personnel, managers and rangers two weeks ago to start planting. They began at the Coffee County park on May 17, went to Cook County’s Reed Bingham on May 18 and ended at Laura S. Walker on May 19. Davidson took the remaining pitcher plants to set out at Little Ocmulgee. “We all had a blast,” Rawlins says, “and a lot of good, very satisfying work was accomplished. Nature cooperated by raining on the plantings.”

During those three days, several hundred sandhill milkweed (Asclepias humistrata) plants, grown by the Atlanta Botanical Garden, and a total of 1,500 pitcher plants and seeds were set out in suitable habitat, safe from development or other use. “The project was specifically designed for planting on Georgia conservation lands where the plants are protected and habitat management is known,” Kruse says.

By planting in state parks, the DNR is able to also engage landowners and other members of the community. “The plants are in areas along trails with public access,” Kruse notes, “and they will provide excellent opportunities for education about the importance of native wildflowers and habitat diversity.” State park personnel will monitor the plants over the summer. For all concerned with the pitcher plants, this is an important experiment. “They are learning how to outplant the pitcher plants, and we’ll see how they do,” Kruse says.

From one bog, rescued by people who are passionate about Georgia’s native habitats, plants and creatures, carefully managed by ABAC, with the collaboration of state agencies and, incidentally, a federal program, these unusual, insect-eating plants may have the beginnings of a comeback in their South Georgia home.

Article by Sherri Butler, June 1, 2016 edition of the Herald-Leader of Fitzgerald, Georgia